Explaining code with RAG

RAG + call graph expansion + LLM = codebase explanations.

I wrote a semantic search tool, then piped the results through an agent to explain algorithms.

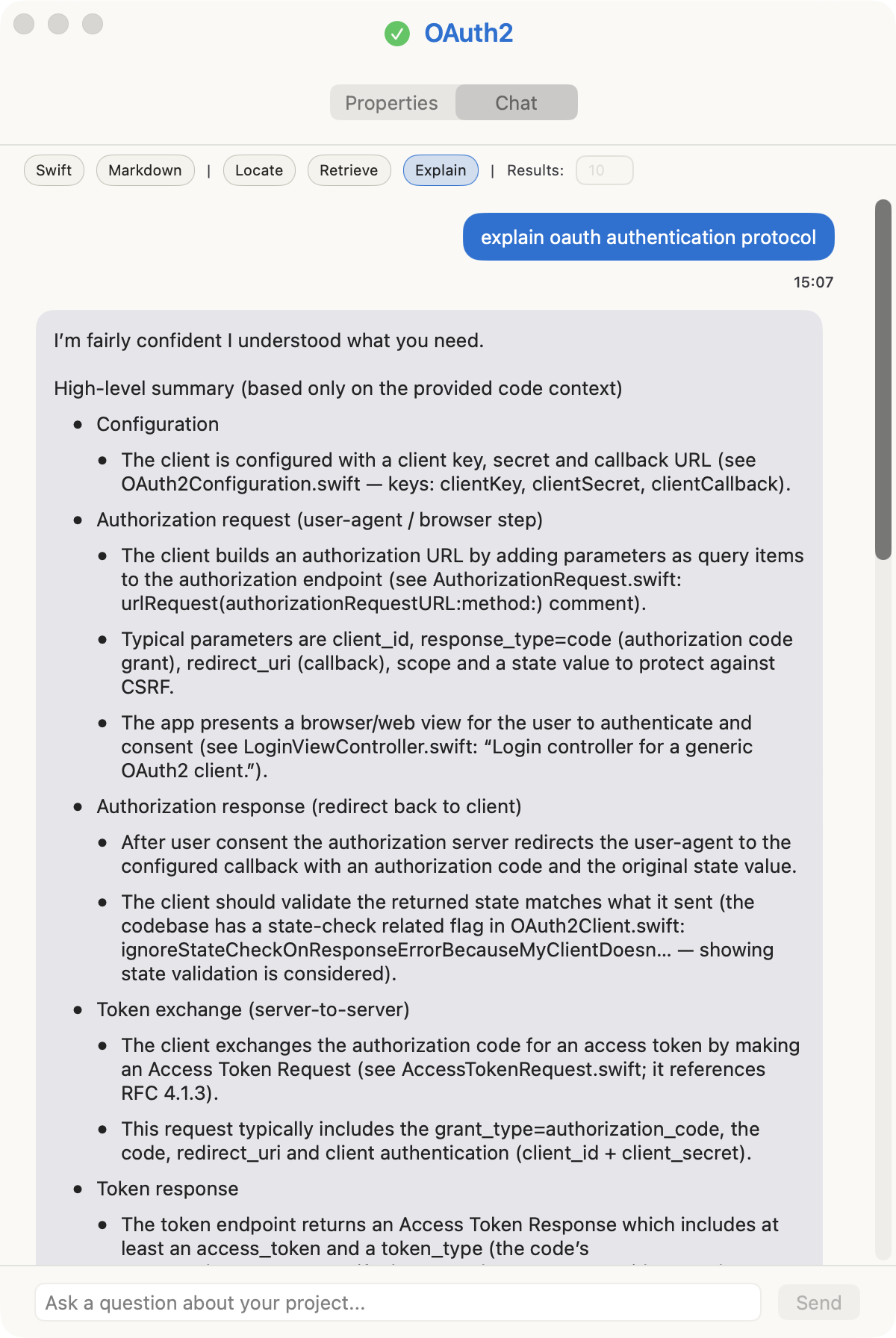

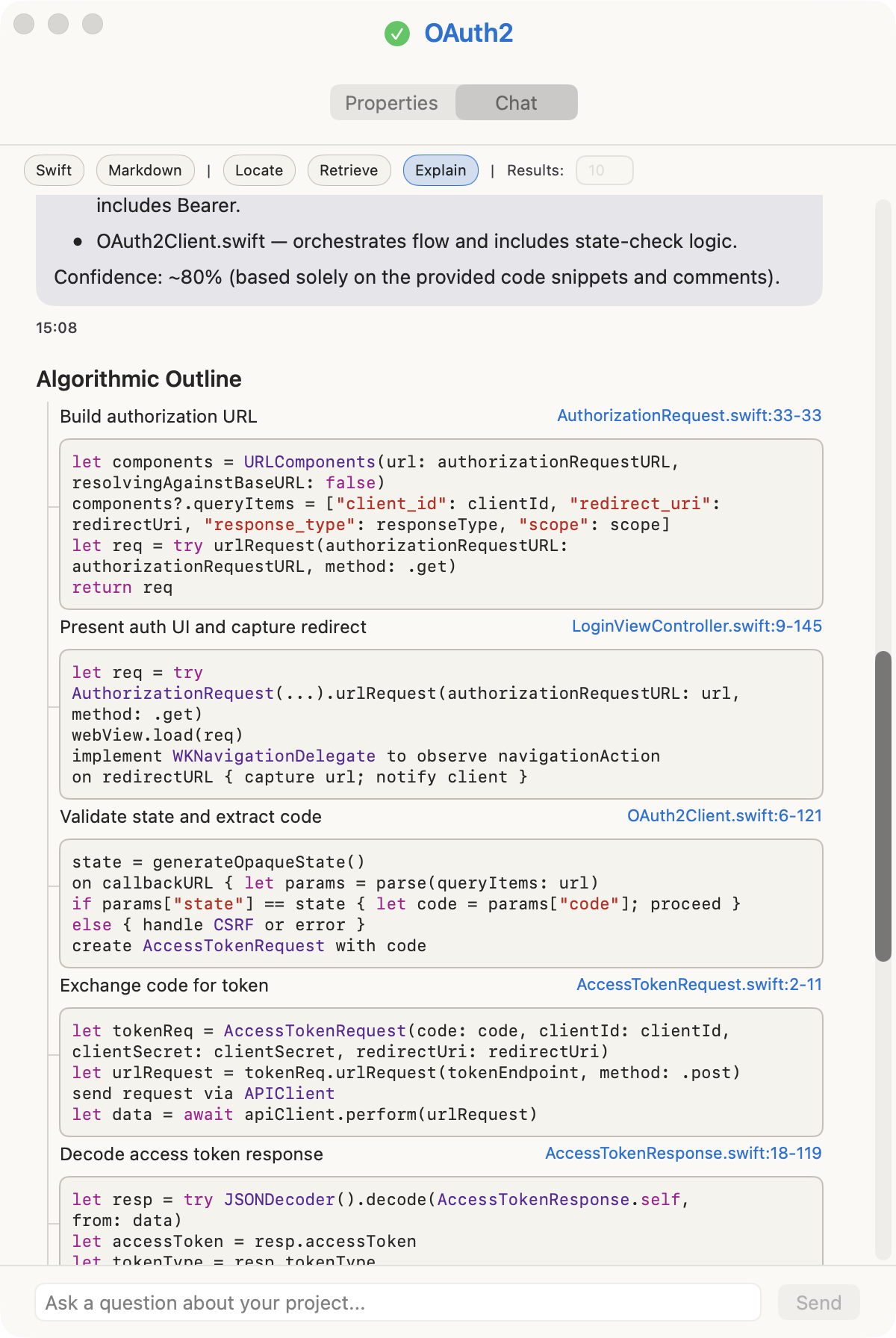

e.g. explain oauth authentication protocol

The answer above was generated solely from a Swift codebase.

The tool selects the relevant information using a combination of semantic search, heuristics, and the call hierarchy graph. Generating an explanation is generally twice as fast as asking a coding agent, and half as cheap.

This implementation is Swift/Xcode-centric. Semly indexes Swift and relies on Xcode’s IndexStore to build a call-graph.

The Problem

I’m trying to answer a user’s question about an algorithm buried in a mid-sized codebase (100–500k lines). The code exceeds the model’s context window, so the challenge is finding the relevant pieces.

An agent approach is to grep synonyms of the query words, evaluate results, then grep further for symbols found until the picture is clear. This is effective—once the agent finds a trail it follows guided by its own intelligence.

In comparison, semantic search is faster and uses fewer tokens. The tradeoff is depth. An agent can continue indefinitely; semantic search gives you a first step. The quality ceiling is lower, but the cost floor is much lower too.

The best results come from combining both: semantic search for initial exploration (it’s an external system, so token-cheap), then let the agent judge whether the answer is sufficient or whether it needs to grep additional details or start over.

From the terminal, run semly explain or outline, and you’ll get a terminal version of the answers above.

~ % semly outline "explain oauth authentication protocol" --project OAuth2

├─ S1 : Start OAuth Flow LoginViewController.swift:9-145

├─ S2 : Build Authorization Request OAuth2Client.swift:6-121

│ └─ S3 : Exchange Code for Token AccessTokenRequest.swift:2-11

├─ S4 : Decode Access Token Response AccessTokenResponse.swift:18-119

└─ S5 : Load Configuration OAuth2Configuration.swift:50-50

Why Semantic Search Isn’t Enough

Semantic search finds code conceptually similar to the query, but ignores the relevancy of the code structure, and doesn’t follow-up the call hierarchy. Therefore, what’s missing here is to expand the call graph of each result, and pick the most likely graph to answer the question.

Building the Index

A required first step is to index the codebase. This inconvenience is why agents don’t implement semantic search.

Chunking

First, it splits files into chunks—contiguous slices of text with a file path and line range.

It is critical to split at semantic boundaries. For source code you don’t want half of one function glued to half of the next, otherwise the resulting code is confusing, and the embedding won’t be representative. I used a parser (SwiftSyntax for Swift) to identify these boundaries. Each chunk represents a coherent unit of meaning. In practice this involved trial and error and dealing with a lot of cases, Swift is complicated.

Markdown, however, was simple: split by sections, paragraphs, tables, etc.

Embedding

The system calculates the embedding for each chunk. It stores each chunk’s text, line range, file path, and embedding in SQLite.

When the user sends a query, the system embeds the query, then looks up similar embeddings in the database. The operation to calculate similarity is called cosine similarity. The result is a list of chunks hopefully related to the user query.

The indexing process interleaves disk I/O with embedding creation, so the CPU is mostly idle. You can leave it running in the background—it scans for changes on a configurable interval (say, 10 minutes) using file modification times, hashes, and file events. Negligible overhead.

Symbols and the Call Graph

Chunks capture text. The source code symbols in that text capture structure.

A symbol is a declaration: a function, method, initializer, computed property, or closure. The indexer extracts these from the syntax tree and stores them with their name, kind, file path, and line span. Closures get a synthetic name like “closure@42”. Importantly, the indexer also extracts call edges—which symbol calls which other symbol.

This gives us a graph. When semantic search finds a relevant function, the tool can ask: what calls this? What does it call? The answer might be more relevant than the original hit.

For cross-file relationships, the system uses USRs (Unified Symbol Resolution identifiers) from Xcode’s IndexStore when available. A USR is a stable identifier for a declaration that works across files and modules. Without it, cross-file callees often remain unresolved.

In order to use the IndexStore, the user must compile the source and then point to its folder within Derived Data. This is done in the application’s UI from the properties of the project. This step exists because some symbols are dynamically resolved and can’t be figured out just by looking at the source. In Swift the compiler always knows what calls what at compilation time, so looking up the store is the only way to get this information. If skipped, the application tries to compensate by favoring locality and lexical overlap (fancy term for string overlap).

The Query Pipeline

When a question arrives, the ‘explain’ feature runs through five stages:

- Retrieval: semantic search for chunks related to the query.

- Symbol mapping: convert chunks to structural units (functions, methods) the system can traverse.

- Graph traversal: walk callers and callees to find code semantic search missed.

- Ranking: score by graph depth, locality, and lexical overlap with the question.

- Context composition: concatenate the top chunks into a prompt the model can use.

Retrieval

The system gathers seeds (initial chunks) from three sources:

- Cosine similarity on the database using query embedding as input.

- Full text search on the symbols of the database using query terms.

- Symbol search in the IndexStore if available.

Step 1 returns embeddings, step 2 and 3 return symbols. The database stores triplets of embeddings, symbols, and chunks, so having one lets you query the others. Then perform an additional step of common sense heuristics: discriminate against test files, CLI boilerplate, and UI scaffolding.

For markdown, the indexer treats section headers as symbols. I didn’t implement PDF because it is not semantically annotated and would require clunky heuristics based on font size, styles throughout the document, and common terms.

Option Enable lexical prefilter. When enabled it discards symbols that lack a string overlap with the query. This is useful if your query mentions a specific symbol you are looking for. Default is off because it lets you type vague queries, which is the most common case.

Graph Traversal

Embeddings, symbols, and chunks are all linked in the database. For instance, a chunk covering lines 50–80 maps to whatever function or method is declared in that range.

Therefore the system can focus on the symbols to build a graph and then traverse it. For source code this means moving in two directions: callers (who uses this?) and callees (what does this use?). In Semly the walk is bounded—depth ≤3, nodes ≤10—to keep results focused rather than sprawling across the entire codebase.

This is where the traversal discovers code that semantic search missed. A utility function might have a generic name and boring documentation, but if it’s called by three of the seed symbols, it’s probably relevant.

Ranking

The expanded set of symbols needs ranking. The ranker combines several signals: graph depth (closer to seeds is better), locality (same file or module), lexical overlap with the question, and embedding similarity.

The system also expands locally: if the graph is thin, it adds neighboring chunks from the same file—the function above and below a hit. This helps when the relevant code is clustered.

The ranking of symbols whose string overlaps with the query is increased. e.g. you asked about a pipeline and there is a class name containing that word.

Option Anchor-only downweight scale. Signatures (or headers) are keyword-dense so they are too boosted by lexical overlap, full text search and cosine similarity. This feature only kicks in when results are signatures only to resurface the bodies. Most times signatures are indexed with their bodies and this is not used.

Context Composition

The top-ranked symbols map back to chunks. The pipeline concatenates these into a single text block with file paths and line hints, trimmed to fit the model’s token budget. This is what the model sees: the question and a curated selection of code. The graph itself is never sent to the model. It’s scaffolding for selection, not part of the prompt.

I’m using a budget of 24k tokens (~1,500 lines of code). How much you should use depends on the quality and number of the chunks retrieved. Since I’m using GPT-5 mini (400k context tokens) you can go to Settings and increase it.

Generating the Answer

With context composed, the system calls the model. The prompt includes the question and the selected chunks. The model generates prose, and because each chunk carries its file path and line range, it can include links that direct the user to the relevant code.

So the full loop is: question → semantic retrieval → structural expansion → ranked selection → grounded answer.

Tuning the Pipeline

I experimented with several options in the form of flags. They are not exposed because they represent the best configuration. I’m showing them here to offer some insight on the inner workings.

Sample query

semly explain "How does the per-file pipeline process a file: chunking → embeddings → transactional DB sync?"

--project Semly

--limit 10

--topK 3

--indexstore-seeding

--oversize-anchors

--include-dependencies

--outline

- –limit N caps the number of anchors (final chunks sent to the model) and the total context size. Lower values produce tighter, more focused answers. Higher values help for broad architectural questions.

- –topK K controls neighbor expansion—how many same-file chunks to add around each anchor when the graph is sparse.

- –oversize-anchors allows large spans when the important logic sits in a single big function. By default, the system caps chunk size to maintain diversity.

- –include-dependencies includes code from packages and dependencies, which are normally filtered to keep focus on the main project.

- –indexstore-seeding enables USR-based seeding and edge repair using the configured Xcode IndexStore. This improves cross-file precision but requires a built project with an up-to-date index.

Beyond flags, I’ve made the selection step more resilient: when the graph is sparse or noisy, explain can fall back to using whole files and focus only on code that’s connected in the call graph. It also drops obvious noise (tests, UI, CLI scaffolding) so the model sees real logic instead of boilerplate. In practice this yields richer context for complex questions without overwhelming the model with irrelevant text.

Outline runs the same retrieval pipeline but asks the model for strict JSON; it takes ~230% longer. Isn’t it wild that 25 years ago we had hierarchy calls for Java but today we need to stitch one together using the IndexStore?

Is this any good?

Locating code is definitely faster during an initial exploration. Claims of “using product X reduces Claude token consumption by 80%” are a cherry pick of this first step.

Explaining code misses more than an agent would. It does better if IndexStore is connected because that provides a true hierarchy of calls, rather than attempting to infer it. I prompted the agent to evaluate its own confidence on the answer and avoid hallucinations.

But it saves tokens. Your main agent gets a more or less accurate version of the algorithm and can continue from there. This is what Claude does already when it uses Haiku to search code.

Note this explain feature presented here is not like Windsurf codemaps. What they do, it seems, is taking part of the hierarchy call graph and requesting a shallow explanation.

Overall, this experiment is a negligible optimization. “You can just ask things,” and live a life without complications. The difference is for initial exploration roughly ~15 seconds and 2% percent on the token context.